Domain V: Collaborate with Clients to Apply a Contextualized, Systemic Lens to Case Conceptualization

CC15 Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Change

Collaborate to target levels of intervention and to co-construct change processes that are responsive to culture and social location.

Recommended Reading

Collins, S. (2018). Collaborative case conceptualization: Applying a contextualized, systemic lens. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 601–616). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

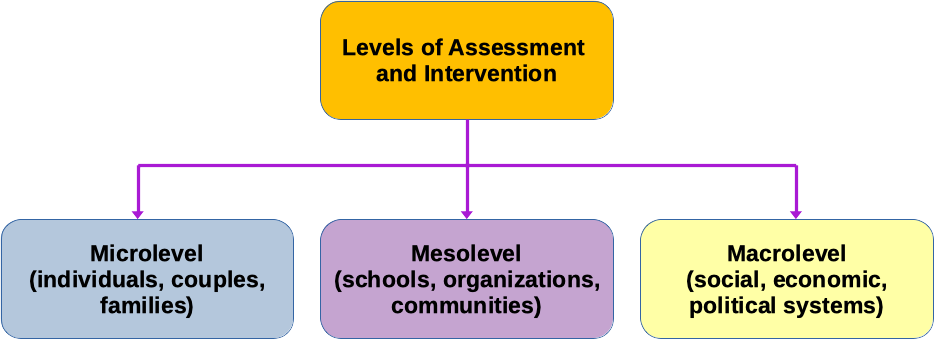

Change is most likely to occur when counsellors negotiate actively with clients to set both the preferred outcomes and the processes through which change will occur. Within the CRSJ counselling model (Collins, 2015), Core Competency 15 focuses the collaborative efforts of counsellor and client on identifying the most culturally responsive and socially just change processes, which may include targeted change in the contexts of the client’s live experiences. Based on the process of case conceptualization, learners can identify the most appropriate locus of intervention, including potential systems level change (Ratts & Pedersen, 2014; Ratts et al., 2015). I encourage learners to consider multilevel interventions at the microlevel (e.g., individuals, couples, families); mesolevel (e.g., schools, organizations, communities); or macrolevel (e.g., broader social, economic, and political systems), and to collaborate actively with clients to establish change processes that are culturally responsive and socially just. This may involve adapting traditional counselling theories, critiquing counselling processes for their cultural relevance and responsivity, and expanding counsellor roles to be more fully responsive (Arthur & Collins, 2016; Houshmand et al., 2017).

CRSJ Counselling Key Concepts

The activities in this chapter are designed to support competency development related to the key concepts listed below. Click on the concepts in the table and you will be taken to the related activities, exercises, learning resources, or discussion prompts.

CRSJ Change Processes

What makes a change process culturally responsive and socially just

Drawing on what you have learned so far about the CRSJ counselling model, create a list of qualifiers that you might use to assess whether a particular change process could be considered culturally responsive and socially just. You may find it helpful to respond to the prompt: Culturally responsive and socially just change process are: [fill in the blank with as many words as you can.]

Once you have a list of at least 12–15 qualifiers, watch the following short video. The story is designed to open up multiple avenues for conceptualizing Giselle’s lived experiences, drawing on the bio-psycho-social-cultural-systemic framework.

Use this story as a starting place for considering what types of change Giselle may envision for themselves and how you might support them, as their counsellor, by co-constructing change processes that are responsive to their personal, family, work, and broader sociocultural contexts. Apply each of your qualifiers as you consider what avenues for change might fit for Giselle. What do you learn from this process? What might you add to your list?

Hopefully, it becomes apparently that any assessment of cultural responsivity and socially just practice must centre on the specific client you encounter, struggling with their particular challenges, which can only be fully understood within the various contexts of their life.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc15/#whatiscrsj]

Etic (Transcultural) Versus Emic (Culture-Specific)

Review the distinctions between an emic and etic approach to counselling below.

The etic or transcultural approach assumes that all human beings share certain common experiences. For example, some multicultural counselling models focus on the shared experience of cultural oppression for members of nondominant populations in terms of cultural oppressions, rather than examining the unique experiences of particular cultural groups such as anti-Indigenous racism. Practice principles emerge through the lens of between-groups similarities. One example is the Canadian Psychological Association (2017) Guidelines for non-discriminatory practice.

The emic perspective is sometimes referred to as a culture-specific or minority-centred approach because it focuses on the lived experiences and counselling needs of particular nondominant groups. It is from this lens that specific guidelines for working with each population arise. Practice principles emerge through the lens of between-group differences (e.g., the unique and specific needs of Indigenous clients or transgender clients). Space is created for culture-specific knowledge and healing practices. Take, for example, the American Psychological Association (2015) Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people.

With your partner, each select one of these approaches, and search for current guidelines related to multicultural counselling practice that would fit best under that broad umbrella. Collect three examples each, in addition to the one listed above.

Then on your own review lightly the examples you found, and make a few notes in response to the following questions.

- What appear to be the strengths of the approach you selected, based on the examples you have identified?

- How might this approach support you, as the counsellor, to identify potential change processes that are most likely to be culturally responsive and socially just?

- What basic principles can you identify to guide your approach to change?

Together, share what you have learned from each approach.

- Discuss how you might merge your learning to inform your work with each client you encounter.

- Reflect on how you would apply the practice principles you identified, while also attending to within-group differences (i.e., the uniqueness of each client’s intersections of identities, relationalities, and social locations).

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc15/#emicvsetic]

Religion and spirituality have only recently begun to be centralized in discussions of multicultural counselling competency. Review the Spiritual Competencies put out by the Association for Spiritual, Ethical, and Religious Values in Counseling (2009). Notice that these competencies apply broadly to working with clients from all religious or spiritual perspectives (etic approach); however, they also embed the expectation that counsellors will honour and create space to integrate each client’s worldviews (emic approach) into counselling practice.

Apply the spiritual competencies to your critical discussion of the following case scenario.

Liz comes to counselling because she has recently lost her partner to cancer, and she is feeling depressed, lethargic, and unable to “get back on her feet.” She describes their relationship as loving, long-term, mutually respectful, and the centre of her life. She can’t make meaning of this loss and is struggling to hold onto any sense of purpose in life. She and her partner retired 15 years ago, after years of working in a not-for-profit agency advocating for persons with disabilities. In the last 10 years, she has developed a degenerative osteoarthritis and is in considerable pain most of the time. She and her partner assumed she would be the first to die. Now, without her partner and with her physical deterioration more rapid of late, she cannot envision coping with the demands of daily life. The only spark of energy you notice during the session is when she talks about the 2015 Canadian Supreme Court ruling on medical assistance in dying (MAID). She notes that she does not believe in an afterlife. Although she positions herself as an atheist, she sees herself as a spiritual person. Her life meaning has always been tied to her relationships, her work, and her sense of contribution to the larger communities to which she belongs.

Attend carefully to your own spiritual or religious worldview, noting any tensions or challenges that may arise for you in working with Liz from within her spiritual values and perspectives. What multicultural and social justice principles might you draw on to ensure you do not impose your own values or worldview on this client? How might you be optimally inclusive of her beliefs, drawing on the Spiritual Competencies. What possibilities do you envision for pathways to change that you might introduce into the conversation with Liz for your shared consideration?

Now that you we have a rich discussion started about working with Liz, let’s change up the scenario. Click here. How might this new information change how you approached your conversations with Liz and the possible change processes you explore?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc15/#clientspirituality]

Levels of Intervention

Take a few moments to reflect on various challenges you have faced over your lifetime. These might be issues that arose at the person, interpersonal, family, educational, work, or community levels. Then think about several people close to you, and consider the types of stressors they have encountered. Next, review the levels of assessment and intervention in the diagram below introduced by Collins (2018).

Position the various challenges or stressors within each of these levels, and reflect critically on what types of change processes might have served you and your companions well. Identify times when you wished you could effect change in the contexts of your lives? Finally, consider the limitations of more traditional intrapsychic approaches to health and healing in context of your lived experiences.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc15/#expandinglevels]

Locus of Change/Intervention

The following series of videos were originally developed to demonstrate specific counselling techniques to enhance a contextualized view on client challenges. The counsellor, in this case, is focused on empowering Bennu to make changes in the contexts of her life, beginning with her family relationships (microlevel interventions). Ss you view this series of videos, consider carefully what other possibilities there might be for Bennu and her counsellor to address Bennu’s challenges from either a mesolevel or macrolevel locus of change or intervention. Sometimes multilevel interventions are most effective in supporting and maintaining desired changes.

Questions for reflection

- How does the counsellor engage Bennu in viewing the challenges she faces through a contextualized, system lens?

- What are the specific contexts that seem to be contributing to Bennu’s sense of being trapped?

- What are the challenges within these contexts that could potentially represent targets of change?

Questions for reflection

- Revisit the contexts of Bennu’s life that are contributing to Bennu’s image of herself as trapped in a box. What might happen for Bennu if these contexts are not considered in the process of counselling (i.e., the locus of change in positioned only within Bennu)?

- How might this focus solely on Bennu’s responses to her environmental challenges limit possibilities for change?

- What might happen for Bennu if she shifts the way she thinks about herself without corresponding supportive shifts in the contexts of family, community, and school?

Questions for reflection

- The counsellor continues to support Bennu to deconstruct and reconstruct her internal beliefs about her potential, which is an important starting point for empowering Bennu.

- What types of changes in the contexts of Bennu’s lived experiences might alter the messages she receives that are life-limiting and disempowering. Be creative in generating as long a list as possible.

- For example, at the mesolevel, the counsellor might consider connecting with the local community centre to talk about integrating career services for immigrant women. This might expose Bennu’s mom and aunties to new possibilities for young women from their community.

- At the macrolevel focus might it be possible to advocate for increased provincial funding for science scholarships for women, with a particular focus on first and second generation immigrants. How might this function has a health promotion approach for other young women?

Each of these ideas is targets expanding your thinking around counsellor roles and possible avenues to support client health and well-being; none of them may be a good fit for Bennu and her vision of change.

Questions for reflection

- Bennu’s initial steps toward change focus on finding ways to shift her relationship with her parents. In what ways does the therapists’ simultaneous focus on Bennu’s self-perceptions and her parent’s perceptions of her open the door to additional loci of change?

- If you were to continue working with Bennu, which of the possibilities you generated for mesolevel or macrolevel change might you consider exploring with Bennu?

- How might you ensure that the these are client-centred responses to Bennu’s specific challenges, in the particular contexts of her life, that are culturally responsive and socially just?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc15/#outsidebox]

Note. Adapted from Fostering Responsive Therapeutic Relationships, by G. Ko et al. (2021). https://pressbooks.pub/responsiverelationships/. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

References

Arthur, N., & Collins, S., (2016). Multicultural counselling in the Canadian context. In N. Gazzola, M. Buchanan, O. Sutherland, & S. Nuttgens (Eds.), Handbook of Counselling and Psychotherapy in Canada (pp. 73-93). Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.

Association for Spiritual, Ethical, and Religious Values in Counselling. (2009). Competencies for addressing spiritual and religious issues in counselling. https://aservic.org/spiritual-and-religious-competencies/

Collins, S. (2018). Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology. Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Houshmand, S., Spanierman, L. B., & De Stephano, J. (2017). Racial microaggressions: A primer with implications for counseling practice. International Journal of Advanced Counselling, 39, 203-216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-017-9292-0

Ratts, M. J., & Pedersen, P. B. (2014). Preface. In M. J. Ratts & P. B. Pedersen (Eds.), Counseling for multiculturalism and social justice: Integration, theory, and application (4th ed., pp. ix-xiii). American Counseling Association.

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2015). Multicultural and social justice competencies. Association for Multicultural Counseling and Development, Division of American Counselling Association website: http://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/competencies/multicultural-and-social-justice-counseling-competencies.pdf?sfvrsn=14